I have more books by John Barth than I do any other author. Nineteen, actually. Seventeen of which are fiction. The other two, The Friday Books, are in my literary non-fiction section. The majority of the texts were accumulated during a brief, but pretty in-depth relationship I had with his work during my contemporary-lit-heavy undergrad degree at Mount Allison University. Most of the editions of the texts I bought–many of which were long out of print–were picked up at a smattering of interesting east coast used bookstores. Specifically, I remember finding quite a few of them at Amy’s Used Books in Amherst, Nova Scotia, and at the old Halifax location of JWD Books.

I have more books by John Barth than I do any other author. Nineteen, actually. Seventeen of which are fiction. The other two, The Friday Books, are in my literary non-fiction section. The majority of the texts were accumulated during a brief, but pretty in-depth relationship I had with his work during my contemporary-lit-heavy undergrad degree at Mount Allison University. Most of the editions of the texts I bought–many of which were long out of print–were picked up at a smattering of interesting east coast used bookstores. Specifically, I remember finding quite a few of them at Amy’s Used Books in Amherst, Nova Scotia, and at the old Halifax location of JWD Books.

The obsession carried over to my time in Victoria, where Russell Books came in to my life (I worked and shopped there), and I was able to complete my collection of John Barth books. Of my seventeen fiction titles, I do actually have some doubles. I have both a pocket book and a trade paperback edition of the short story collection Lost in the Funhouse (The first Barth book I read). I also have multiple paper back editions of The End of the Road, one of his early novels, and The Sot-Weed Factor.

JOHN BARTH(S)

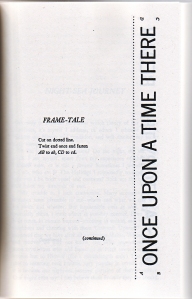

“Frame Tale” is the opening story from Lost in the Funhouse (1968). The text tells you to cut along the dotted line and connect the opposing corners. It forms a moebius strip that reads “Once upon a time there was a story that began Once upon a time there was a story that began Once upon a time…”

In terms of his literature, there are actually two fairly distinct Barths. The first, more darkly humorous, yet formally traditional Barth, published a handful of plot-heavy nearly absurdest yarns starting in 1956. Despite heavy existential themes, his books were playful and even shallow in some ways, but became increasingly complex and cryptic in the early 60s. Yet despite their complexity, they were often driven by fast-paced almost frantic prose.

In the late 60s, specifically after the publication of his 1967 essay “Literature of Exhaustion”, Barth became (in)famous for his helping shape late 20th century postmodern literature. Although he won a National Book Award for his novella trilogy Chimera in 1973, his overly intellectual metafictions began to alienate readers in the 80s, most notably Letters, a massive, dense tome that contains a series of letters between characters from his previous books and the author himself, and is the most overt representation of his deconstructive bent.

MY CONNECTION

When I was first introduced to John Barth, I was an undergrad and completely enmeshed in contemporary lit and theory. I fell in love with his experimental short story collections such as Lost In the Funhouse (this remains an incredibly important work for me, and, I believe, is a landmark of late 20th century fiction) and On with the Story. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve mostly lost interest in his experimental work and have moved back to his more traditional, yet cynical, novels from the 50s.

His work was so influential to me (and I encountered it at such an influential time of my life) that I actually have the cover of the 1967 Bantam paperback edition of The End of the Road tattooed on my arm (there was an apparently really strange film adaptation made of this book starring Stacey Keach that I have never seen). But his influence pops up in other aspects of my life as well.

Perhaps most notably, a copy of Barth’s first novel, The Floating Opera briefly appears in the title story of my short story collection David Foster Wallace Ruined My Suicide and Other Stories. In it, the novel is being read by a bookstore owner that the protagonist frequents. My story, obviously, is about suicide, and Barth’s novel is about a character who wakes up one morning deciding that will be the day he takes his own life: the novel charts his consideration of this idea over the course of that day. The novel was both thematically and tonally an influence on my title story.

Just in case you haven’t read either my story or Barth’s novel, I won’t tell you how either ends.